- Visitor information

- About us

- Exhibitions

- Temporary Exhibitions

- Permanent Exhibitions

- Past Exhibitions

- 2019 / 2020 Shine! - Fashion and Glamour

- 2019 - 1971 – Parallel Nonsynchronism

- 2018 – Your Turn!

- 2018 – Still Life

- 2017 – LAMP!

- 2017 – Tamás Zankó

- 2017 – Separate Ways

- 2017 – Giovanni Hajnal

- 2017 – Image Schema

- 2017 – Miklós Szüts

- 2016 – "Notes: Wartime"

- 2016 – #moszkvater

- 2015 – Corpse in the Basket-Trunk

- 2015 – PAPERwork

- 2015 – Doll Exhibition

- 2014 – Budapest Opera House

- 2013 – Wrap Art

- 2012 – Street Fashion Museum

- 2012 – Riding the Waves

- 2012 – Buda–Pest Horizon

- 2011 – The Modern Flat, 1960

- 2010 – FreeCikli

- 2008 – Drawing Lecture on the Roof

- 2008 – Fashion and Tradition

- 2004 – Mariazell and Hungary

- Virtual museum

- What's happening?

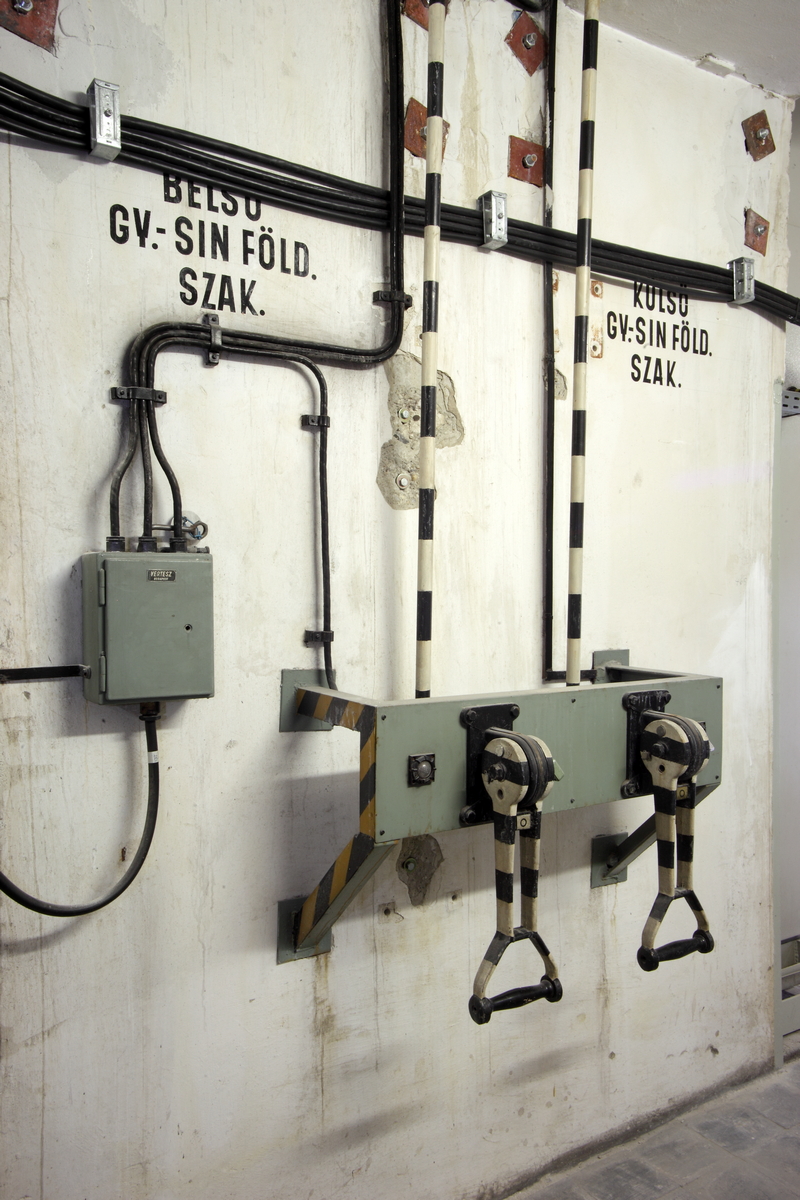

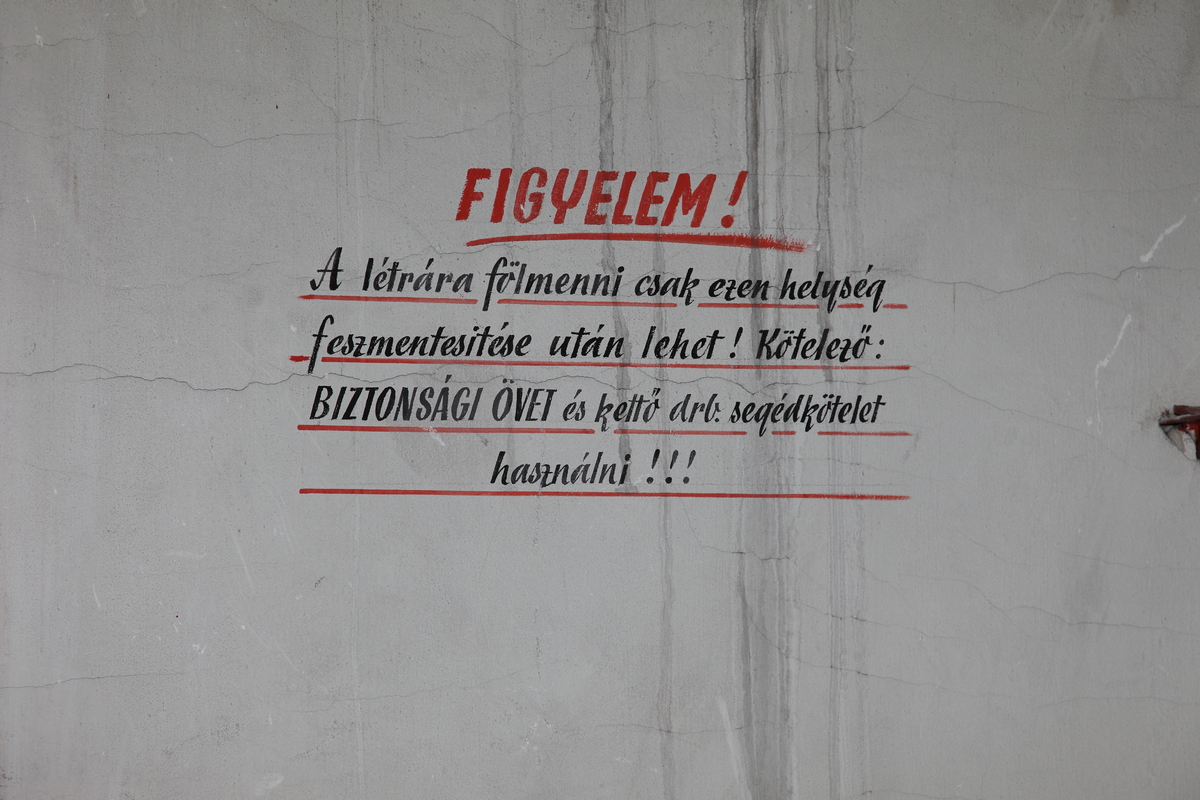

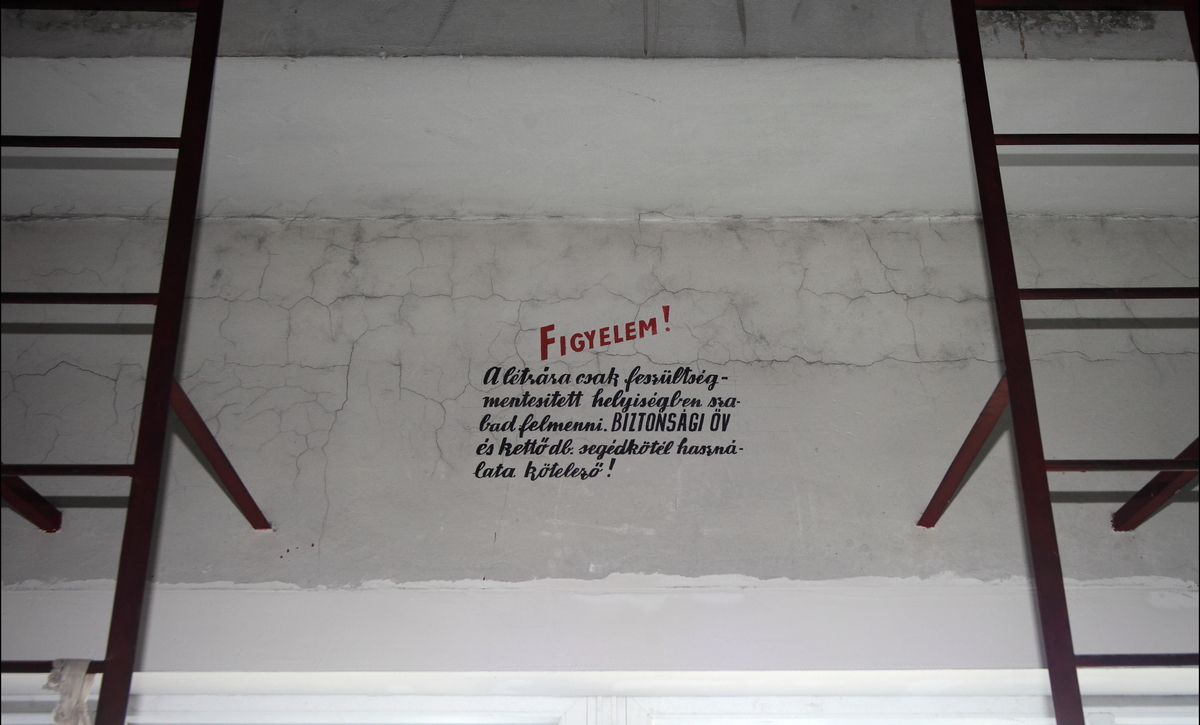

Dob Street Electrical Substation

Dob Street Electrical Substation

1072 Budapest, Dob utca 10.

Architect: Ernő Léstyán (ERŐTERV)

Mechanical engineer: Dezső Herczegfy (ERŐTERV)

Technological engineering: József Babonits

Planning: 1963–64, construction: 1965–68

Documentation: February 2020 (cc. 240 photos)

Photos: Judit F. Szalatnyay, concept: Márta Branczik, contributor: Csaba Gál

Photo description consultant: Csaba Pánczél, ELMŰ

The documentation of the building was conducted in collaboration with the Hungarian exhibition project Othernity - Reconditioning our Modern Heritage at the 17th International Architecture Biennale.

Contemporary sources:

L. E. (Léstyán, Ernő): Erzsébetvárosi transzformátorállomás, Budapest VII., Dob utca. [Erzsébetváros Electrical Substation, Budapest, District VII, Dob Street.] Magyar Építőművészet, 1970/3. pp. 29–30.

Arnóth, Lajos: Megjegyzések a transzformátorállomás kapcsán. [Comments on the substation.] Magyar Építőművészet, 1970/3. pp. 31–32.

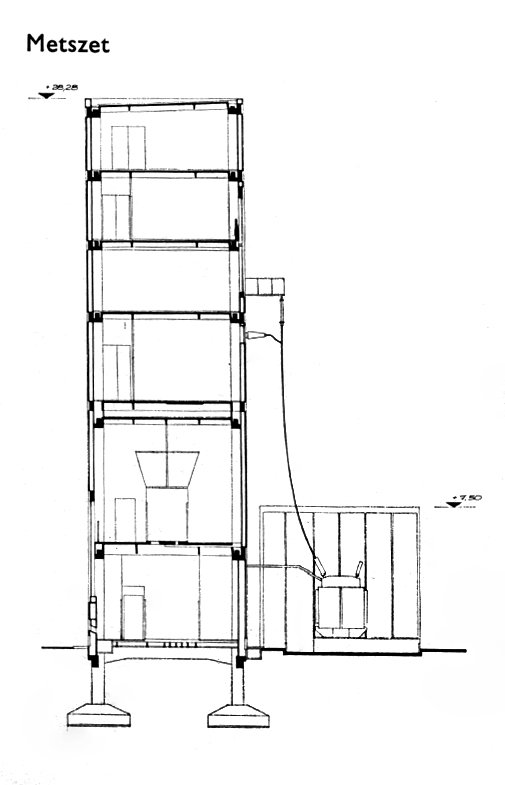

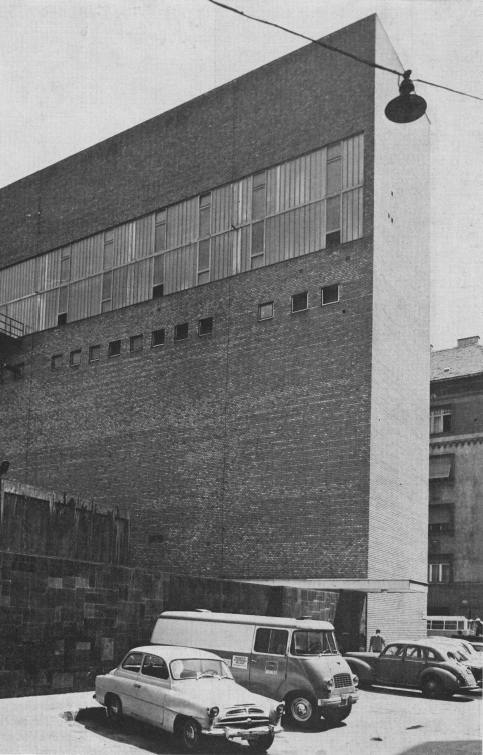

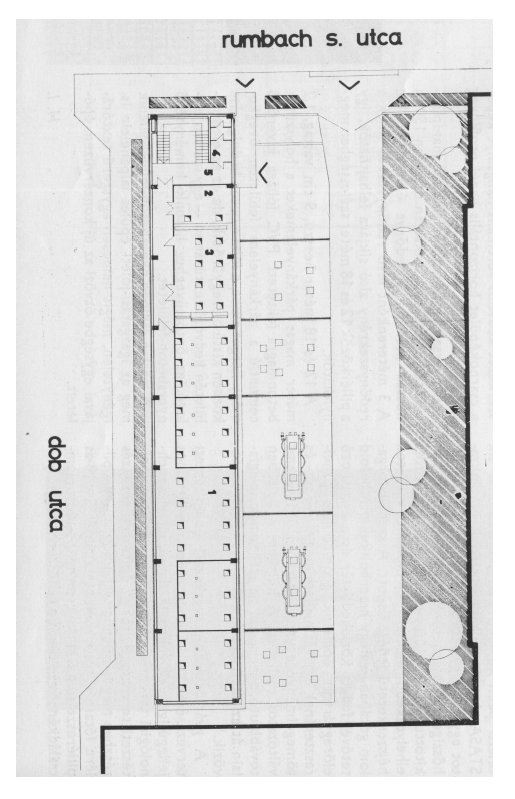

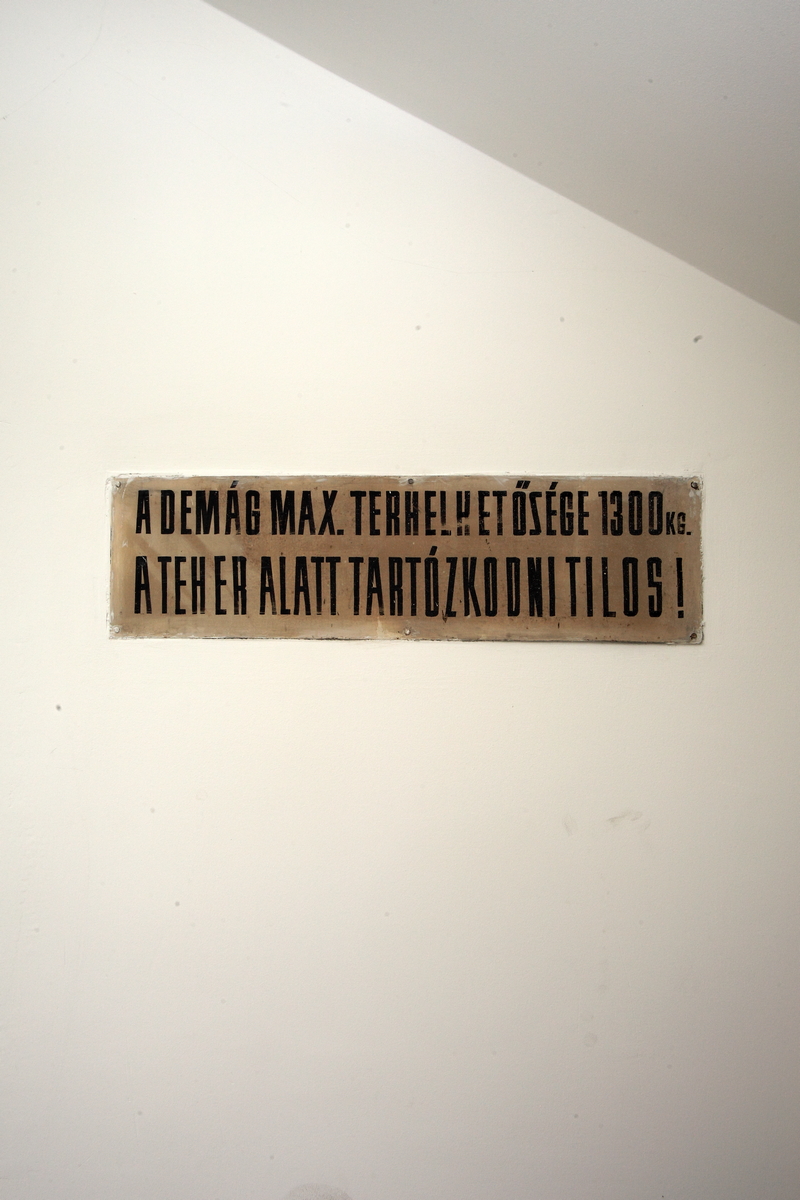

Budapest's increased demand for electricity has necessitated the construction of more and more electrical substations throughout the 20th century. For technical reasons, these facilities had to be integrated into the fabric of the city, and this naturally raised the question of their relationship with the already existing architectural character of the city. What would an industrial building look like in the middle of the city, among residential buildings? The 1960s approach, rooted in classical modernism, was that the form of a building should not be at odds with its function. ‘Both the honesty and the technical requirements of the building contradict the camouflage of which the substation in Óbuda is a typical example,’ said a contemporary critic, referring to Dénes Györgyi's transformer station on Szentendrei Road, built in the 1930s. To be fair, Györgyi had designed an art deco substation in Markó Street in the late 1920s, in keeping with his own era. Léstyán had similar ideas, building the composition according to the principles of modern architecture, using simple geometric masses, with minimal but carefully placed openings in the facade surfaces. The first of the new subtations he designed was the one in Ferencváros, on Csarnok Square (1965), and in the same year the construction of the station in Erzsébetváros was started. Due to the environment and the limitations of the site, the frame structures, slabs and partition walls of the building were made of prefabricated reinforced concrete elements, while the brickwork wall and the cross-sectional brick paving were made on site. The main mass of the building is a single, narrow-sided brick body, the street façade on Dob Street originally articulated by a continuous band of profiled glass panels and a series of vertically stacked vents. On the façade facing the lot, visible from Rumbach Street, the main floor is marked by square windows (now extended with an oblong window), above which is a row of converted two-storey openings with four associated “technical balconies”. The halls on each level are lit from one side only – levels 1-2 from the Dob Street façade and levels 3-4 from the Rumbach Street façade –, so that one level is lit from above and the one above it from below. This solution may suggest that the division of the façade is not merely a matter of functionality, but rather an aesthetic choice – Léstyán thus avoided the monotonous window distribution typical of industrial buildings.

The entrance is on the Rumbach Street side of the property, and the 132kV transformers are located in the courtyard outside the building. The entrance to the building is marked by a cantilevered canopy on the black polar quartzite (?) clad fence wall. As the station is remote-controlled, there are hardly any offices or communal spaces in the building, but there were two service apartments on the 3rd floor. The view from these would have been the envy of anyone!

GALLERY:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to the main page: Virtual Architectural Salvage