- Visitor information

- About us

- Exhibitions

- Temporary Exhibitions

- Permanent Exhibitions

- Past Exhibitions

- 2024/2025 - Life with Honey

- 2024/2025 - WANDERINGS - Lili Ország in Kiscell

- 2024 - Light & City

- 2022 - Gábor Gerhes: THE ATLAS

- 2019/2020 - Shine! - Fashion and Glamour

- 2019 - 1971 – Parallel Nonsynchronism

- 2018 – Your Turn!

- 2018 – Still Life

- 2017 – LAMP!

- 2017 – Tamás Zankó

- 2017 – Separate Ways

- 2017 – Giovanni Hajnal

- 2017 – Image Schema

- 2017 – Miklós Szüts

- 2016 – "Notes: Wartime"

- 2016 – #moszkvater

- 2015 – Corpse in the Basket-Trunk

- 2015 – PAPERwork

- 2015 – Doll Exhibition

- 2014 – Budapest Opera House

- 2013 – Wrap Art

- 2012 – Street Fashion Museum

- 2012 – Riding the Waves

- 2012 – Buda–Pest Horizon

- 2011 – The Modern Flat, 1960

- 2010 – FreeCikli

- 2008 – Drawing Lecture on the Roof

- 2008 – Fashion and Tradition

- 2004 – Mariazell and Hungary

- Virtual museum

- What's happening?

Art Piece of the Month

2018/July-August – Tibor CSERNUS (1927-2007): Reeds

1964, oil and collage on canvas, 52,8" x 59,8"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

Tibor Csernus, a student of Aurél Bernáth, following in the footsteps of the modern Hungarian masters gathered in Nagybánya from 1896, developed his style based on the tendency of realistic depiction. His artistic views were strongly influenced by his trip to Paris in 1957, during which he became acquainted with the latest inventions of modern French art. For years, he was considered the leader of the so-called Surnaturalist movement.

This painting is a peculiar example of Surnaturalism. On its surface, created with a variety of tools - sponge, painting knife, razor blade, etc. – several techniques coexist, such as gestural abstraction, printmaking or collage. His painted surfaces of the time are characterized by figures and objects depicted in a feature-rich, surrealistic detail, wrapped in pure, vibrant fields of colors, giving different emphasis for each pictorial element. Thus, the visual elements are far from being merely signs of themselves in the works of Csernus. We can admire a seemingly idyllic scene: there is a cheerful gathering on a gangplank at a summer lake. But if we look a little more carefully, it turns out that nothing is going right. The high horizon – as well as the title – draws attention to the swampy, boggy brake in the foreground. Above a sunken boat and a floating corpse, on the gangplank, the feast turns into a Bacchanalia. All this faithfully reflects the lost Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and the connivance between Hungarian society and the Kádárian leadership in the early 1960s. The moral account is dovetailed with a ruthless self-criticism: from the virtuously formed orgy, reminiscent of a butcher counter, the face of the artist emerges, suggesting that there is no one on earth who never sins.

Due to conflicts with the regime, Csernus became marginalized, and finally was given the right in 1964 to leave Hungary – which was a synonym for expulsion at the time. While settling down in Paris and continuing his career as a world-renown painter, his art grew more traditional. Along with his Hungarian stay, his Surnaturalist period came to an end.

2018/June – Károly LOTZ (1833-1904): A Bridge in Rákospalota

1879; oil on canvas; 38,2" x 57,9"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

One of the most esteemed Hungarian painters, Károly Lotz’s oeuvre is mostly recognized due to his mural works (Concert Hall, National Museum, Keleti Railway Station, Opera House, St. Stephen's Basilica, and Parliament House) as well as his portraits and nudes today. However, he exhibited landscape pieces (both in Budapest and Vienna) even at the start of his career, especially paintings depicting the Great Hungarian Plain. However, the workload stemming from his regular commissions often overshadowed this aspect of his oeuvre. From the 1870s, he was a regular guest in Káposztásmegyer, residing in the villa of his old friend and painter, Károly JAKOBEY, and made excursions to the neighboring towns of Rákospalota, Fót, and Alag. The still unregulated streams named Rákos and Szilas invited the artist to paint several watercolor and oil paintings.

This particular piece is the most elaborate one of this aforementioned group. The idyllic genre piece is from the end of the era when Budapest-based artists started to discover the still untouched and natural surroundings and suburban areas of the capital. Of course, the landscape in the painting is beyond unrecognizable today due to extensive urbanization in the past 120 years. Presumably, the scene depicts the bridge and the surrounding area over Szilas stream in Old Fót Street in the 15th district.

The mature landscape paintings of Károly Lotz were inspired by several sources, including the Barbizon school and the old Masters, such as Rubens' landscapes. In addition, Lotz’s artwork is not only a good example of Hungarian romantic landscape painting – painters of the later artists’ colonies of Nagybánya and the Great Hungarian Plain also acknowledged their predecessor in Lotz.

2018/May – Imre BUKTA (1952-): Landscape

1989; paper, mixed tehnique; 28,6" x 40,1"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

Even at early stages of his career, Imre Bukta has always been fascinated by the developments of the Hungarian countryside, the lifestyle of people involved in agriculture. Using various visual elements from this milieu, he creates works that boldly blend techniques. The imagery is based on a certain stylized sowing, created from automatic, repetitive features that is reminiscent of his earlier creative periods. The fragmented horizon and the perspective that employs multiple viewpoints show an unstoppable disintegration of peasant life that was almost unchanged for centuries. The mirage-like planets, shapes and objects are not only playful products of Lajos Vajda Studio’s Neodada tendencies but they are also absurd elements of a rural but not-yet-entirely-gone past. The house in the upper half of the painting becomes a symbol of the discrepancies of general progress and various developments in Central and Eastern Europe. On the other hand, the the bull attacking a farmer and an all-consuming dark balloon shape (from a well-known Hungarian fairy tale) carry ancient agression and represent accumulated tragedies at the same time. In the painting’s context, scattered, hidden streams and blood vessels stand for unprocessed historical deficiencies. The man kneeling in the middle accepts black rain as a religious gift, which is actually the result of a biogeochemical cycle in a polluted environment. According to Bukta, the invidual is powerless against the rampant violence of nature, but they are also responsible for creating such an environment. Not suprisingly, the title itself has several meanings as well: the painting is more than a simple depiction of a superficial sight. It also provides a deepened, abstract image of the peasant landscape, a sincere confrontation and introspection in the year of the change of regime, the end of Communism in Hungary (1989).

Characterized by bitter, grotesque irony but also by loving care, Imre Bukta’s depiction of the Hungarian countryside proves to be relevant even today. In 2012-2013, he set a record among contemporary Hungarian artists: his exhibition "Another Hungary" in Műcsarnok (Kunsthalle) was seen by more than 22.000 people.

2018/April – György KONECSNI (1908-1970): Composition

c. 1965, oil on paper, 39,7" x 38,2"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

Although György Konecsni was primarily known as a designer of posters and stamps, as a former Gyula Rudnay disciple, he did not forget his picturesque roots. The duality of traditional figurative representation and the experimentation with geometric, surrealistic forms is present throughout his career. This particular piece can be perceived just as much as a color study or landscape sketch as it can be seen as an abstract composition. It was painted in the mid-1960s when Konecsni’s attention turned to large-scale public space works, characterized by inventive, unusual posters. During this period of experimenting, he found a new picturesque vocabulary, similar to the expressive tools of his fellow artists who emerged in the same period and who had been cast aside earlier by cultural policy, such as Endre Bálint, Dezső Korniss and Lili Ország.

2018/Easter – Imre BAK (1939): Easter/Kiscell I-II

1994; canvas, acrylic paint; 78,8" x 111"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

On the monumental diptych of Imre Bak, the abstract, stylized image of the former Trinitarian monastery on the hills of Óbuda (today Kiscell Museum) is made up of a bright and cheerful fields of color, in accordance with the artist's late period.

The floating-flowing organic shapes around the cuboid building raise the former Baroque church area of Kiscell Museum to a special metaphysical level. The forms symbolize both the former religious and the current "desacralized" usage of the space. The former monastery, serving different yet noble and intellectual purposes today, is sanctified through the universal celebration of the Easter. Bordering color fields give a sense of perspective to the composition.

Imre Bak is one of the most respected members of the Hungarian Neo-Avant-garde group called 'Iparterv'. From the early 1970s, along with his fellow artists of the generation, they developed a comprehensive program of creative arts and crafts for artists of visual genres, with a great emphasis on improving the aesthetics of the everyday human environment. In Bak's oeuvre, geometric shapes form color harmonies, hue combinations, and abstract landscapes, based on international and Hungarian Avant-garde traditions as well as motifs of Hungarian folk art.

The painting was bought from the artist in the year of painting.

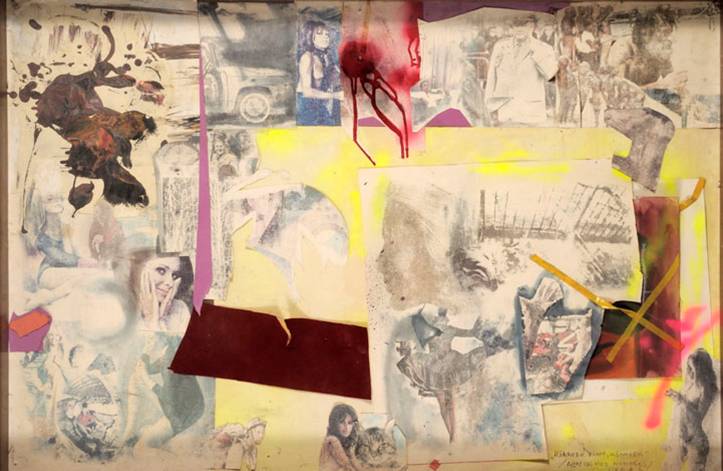

2018/March – Sándor ALTORJAI (1933-1979): Tears My Dear, Tears (Aleatoric Montage No. 6.)

1960/1979; mixed technique, collage on fiberboard; 37,4" x 57"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

Sándor Altorjai is a prominent representative of Hungarian New Expressionism and Pop Art. In his works he often uses elements of photography and film. The title of the "Aleatoric Montage" series comes from a musical term: the author does not define all the details of his work. Like an improvising player, he compiles the imprints of his era like a mosaic: from torn or cut out pieces of paper, without any explanation. However, his choice of materials is very conscious. The printed photos were fixed on paper with chemicals, and the foggy, mind-boggling universe of these secondary prints is juxtaposed with vivid, abstract surfaces. By doing so, he simultaneously integrated mass production methods in his practice and broken their monotony. In 1979, already struggling with fatal illness, he reorganized and completed his œuvre. Many of his works, including this image, found his final form during that year.

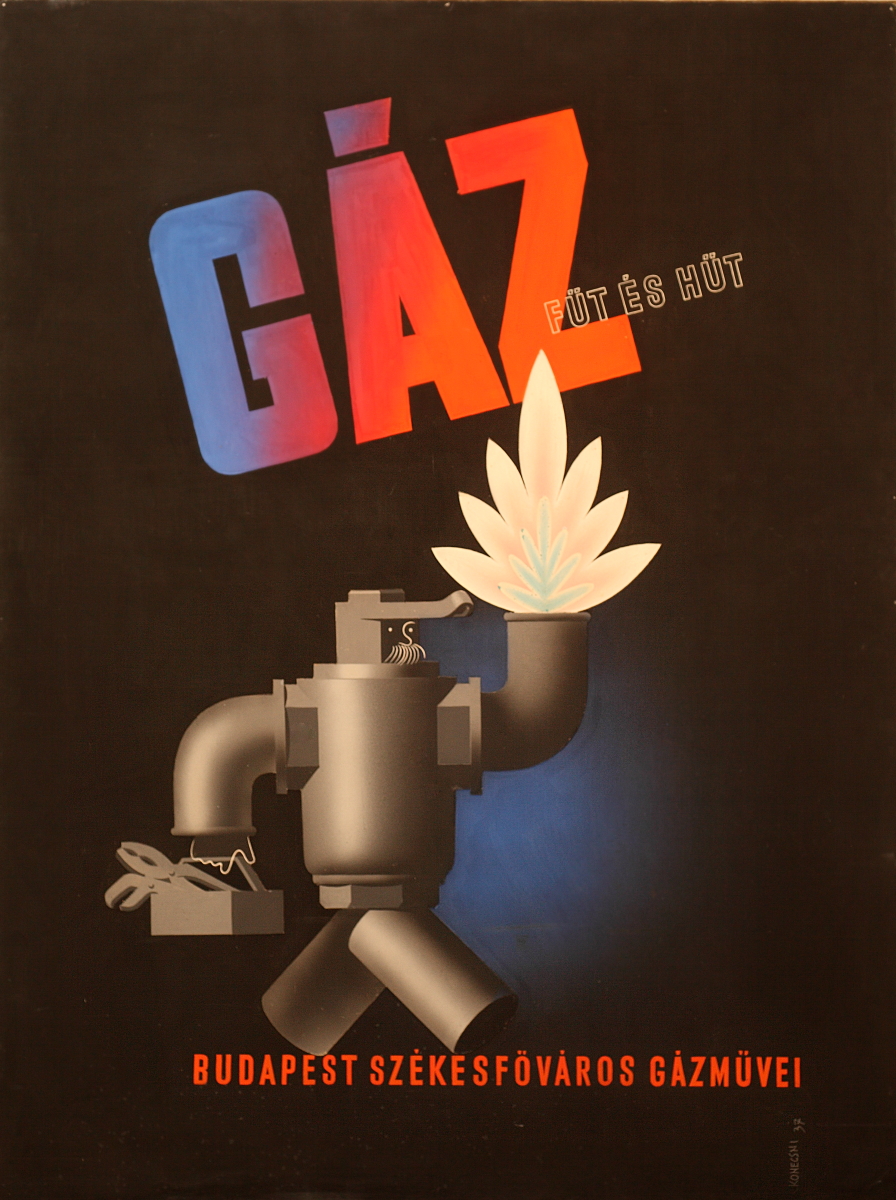

2018/February – György KONECSNI (1908-1970): Gas – It Heats and Cools

1937/1968, tempera on paper and fiberboard, 47,2" x 35,4"

Photo: Judit Fáryné Szalatnyay

Konecsni, who originally started as a painter, was primarily known since the early 1930s as a stamp designer as well as a graphic designer, specializing in advertisements. Throughout his career that spanned many political systems, he was often awarded both domestically and abroad. In 1946, he was the initiator of Department of Applied Graphics at University of Fine Arts of Budapest and he also led it until his death. Consequently, members the graphic designer generation emerging after 1945 in Hungary were his students most of the time. Konecsni’s mural works and large-scale mosaics are housed by many public institutions.

Using very few motifs and experimenting with techniques and genres, his posters quickly attained worldwide recognition, also owing to the fact that he consciously applied elements of modern mass media in his advertisements. One of Konecsni’s best-known works was made for the gasworks of Budapest. The figure of the gas-fitting robot used to be among the most popular Hungarian advertising mascots: it was reproduced in many formats, including the neon sign that stood on Erzsébet Square until 2005. For the sake an exhibition held in the Műcsarnok (Kunsthalle) in 1968, the artist re-painted the original plan for this poster.

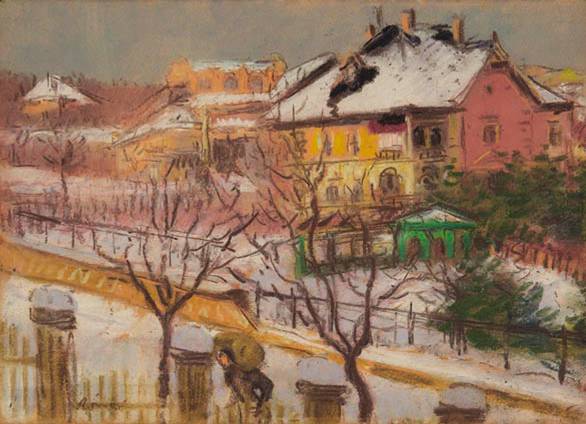

2018/January I. – József RIPPL-RÓNAI (1861-1927): Kelenhegy Road in Winter

1924; pastel on cardboard; 11" × 15,7

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

József Rippl-Rónai, who returned from Paris to Kaposvár, soon needed a studio in Budapest for winter stays. From 1906 he maintained a studio apartment at the Studio House on the Gellért Hill, designed in Art Nouveau style by Gyula Kosztolányi-Kann, that is still in existence and function today. The studio soon became a meeting place for the art scene of the time. In general, he had been living there from autumn to spring, and therefore most of its Budapest landscapes depict the winter view from his studio.

2018/January II. – Béla KÁDÁR (1877-1956): Detail of Óbuda

c. 1916; tempera on paper; 22,8" × 26,4"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

At the peak of his career, Béla Kádár had a solo exhibition at Herwarth Walden's legendary Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin. Thanks to Walden, he was given the chance to exhibit in New York with Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Marc Chagall among others. During the Second World War, however, he was forced to hide with his family because of his jewish origin, and lost his wife and children. After the political turnaround at the end of the 1940s, he was isolated from the Hungarian art scene, and became almost forgotten. His works were brought back to attention only after the change of regime in 1989.

While he fought as a soldier in the First World War, he did not give up on his artistic pursuits and worked on mural commissions. In his paintings from this period, he returned to Óbuda, to the scenes of his difficult childhood several times.

2018/January III. – Leopold STEINRUCKER (1801-1879): Crossing the Danube

1842; oil on canvas; 17,5" × 13,5"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

On the romantic painting of the renowned Viennese painter, in the midst of a much harder winter, the masses of the growing Hungarian capital are forced to risk their lives on the Danube, going from one side to the other. The demand for a permanent bridge has risen. It was in the very year of the completion of the painting that the Chain Bridge’s foundation stone was laid, but the bridge was finally opened to traffic only in November 1849. This work, some years after of the finishing touches, became a document: in May 1849, the palaces on the Pest side of the Danube with the first Vigadó fell victim to the artilleryfire of the Austrian Major Hentzi defending the castle of Buda against the Hungarian army.

2017/December – Mihály MUNKÁCSY (1844-1900): Portrait of Béla Berkes Gypsy Primo Violinist

1895; charcoal on canvas; 31,9" × 25,6"

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

Having worked mostly in Paris from 1867, Mihály Munkácsy was strongly influenced by both the way of perception and the technique of Gustave Courbet. He developed Courbet’s legacy in his last period, partly in the direction of symbolism, partly towards plein air painting, while constantly keeping in touch with his homeland. By boldly mixing the graphic and painting techniques, the cool and informal style of this special portrait, advanced the modernity of the 20th century. The image was dedicated to his younger colleague, Kornél Herzel.

Béla Berkes was one of the most renowned Gypsy musicians of his time, and was born of a renowned musician dynasty. He was the leader of the gipsy band of the National Casino, just like his father and later his son. He performed before the most distinguished audience both at home and abroad, playing for the Prince of Wales and in the Vienna court, among others. Munkácsy depicts the musician in a black tail coat and a white shirt, suitable for the exclusive performances - perhaps recalling the great concert at the 1889 Paris World Exposition.

2017/November – László PAÁL (1846-1879): Forest Detail with Rocks

c. 1874, oil on canvas, 23,4" x 27,2", restored by Ferenc Springer

Photo: Ágnes Bakos, Bence Tihanyi

László Paál, 'the painter of forests' settled down in Barbizon, near to the Forest of Fontainebleau in 1873. This is the period when forest landscapes became the primary theme of his mature paintings. The Forest of Fontainebleau reminded Paál of his homeland in Transylvania: the current piece can be traced back to the years of Paál's first successful exhibits at the Salon of Paris.

Although elements of classic Barqbizonesque landscape paintings can be observed, yet the sunlit young beech forest, the brownish autumn foliage, the glowing skyline, the moss-covered rocks, the passionate depiction of the green-rusty lawn all transform the forest depiction into a lyrical self-portrait. Although Paál's art is closer to earlier Barbizon masters such as Diaz or Corot, the passion of his color usage can also be associated with the great French Impressionists who worked roughly in the same period in Fontainebleau.

The painting was purchased from a private collection in 1970.

2017/October – Jakab WARSCHAG (active 1819-1873): The Prodigal One. Trade Sign of the Little Dirty Pub

1840s, oil on wood, 73,2" x 27,6"

Photo: Dóra Fekete, Edit Mikó

The painting was restored in cooperation between Budapest History Museum and Hungarian University of Fine Arts, under the professional supervision of Dóra Fekete and Edit Mikó in the academic year of 2016-2017.

The fairy tale Der Verschwender, a play by Ferdinand Raimund was premiered in 1837 in Vienna and in 1838 in Pest at the First Hungarian Theater (Pesti Magyar Színház) in Hungarian translation. The painting presumably depicts the beggar played by Miklós Udvarhelyi, a member of the National Theater's company.

The Little Dirty Pub on Curia Street probably opened its doors around 1880. However, the exact date remains unknown. The fact that this painting served as trade sign, hanging in the beer hall of the pub, is known thanks to oral tradition in the seller's family. (They did, however, identify the actor in the picture with Alexander Girard, but he had played the role in particular later than the completion of the painting.) It is very likely this piece was originally used in another hospitality establishment, the so-called Snail Restaurant, a gathering place for writers and actors of Pest on the former Sebestyén Square. The later National Circle, then the Opposition Circle, which had a great impact on Pest's social and political life, were formed out of this company of friends. After the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Mihály Schwetz was the owner of the Snail Pub from 1880 to 1897, the year of its closure. It was his son István Schwetz who bought the pub Little Dirty and Warschag's painting was most likely relocated to its new place at that time.

Jakab Warschag was a well-sought-for painter in his own time, his main profile being trade sign painting, but he also dealt with portraits and religious paintings. His master was stage painter Hermann Neefe (1790-1854). His decorative, appealing colors, antique backgrounds, classicist, idealistic features are easy to appreciate. His work, however, proves his sophisticated portraiture and the influence of Romanticism. The collection of the Municipal Gallery stores more pieces of his oeuvre, and three paintings of his are even on show in the permanent exhibition.

Translated by Magdolna Gucsa.